Today I spoke at a fun little referendum as part of UK:RIP at CPT. The lovely Brian Logan hosted, and speakers were Richard DeDominici, Chris Thorpe, and Thomas Martin. They were all great. Here are the words I said in reaction to the invitation to write a provocation about the indie referendum. The picture is by Richard, who was super funny. As usual, I took it tiresomely seriously.

There are two ways to a world without borders.

One is expanding countries into unions into continents into international bodies.

The other is greater and greater devolution.

Until we reach the unit ‘a person’, and the understanding of our relationship to others

through contexts other than crossings;

the sounds our voices make,

the way we look when we do new thinking,

how we co-operate when individuals don’t fade into a superstructure of taken for granted survival

But are there in front of us, swapping us solar energy surplus for some of these fine potatoes.

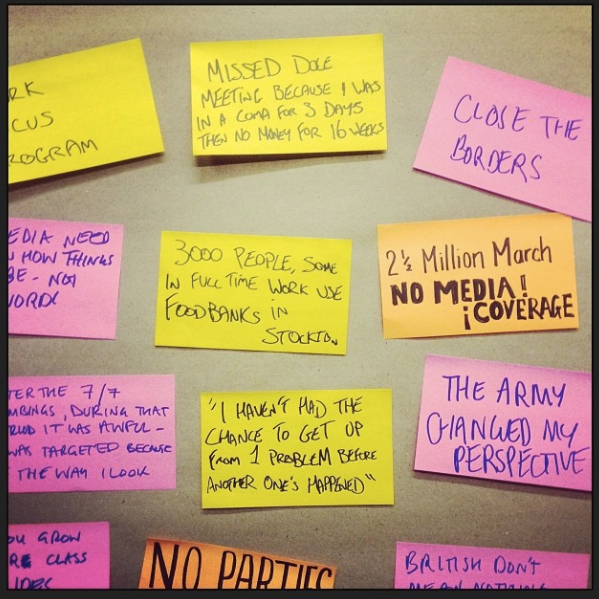

At the beginning of this year I made a new piece of theatre

which involved talking to people in the street about what Britishness meant to them.

I spoke to people in London, Bradford, and Stockton on Tees.

I hope to tour this piece talking to more and more people as we go.

But as for these three cities.

London, Bradford, and Stockton on Tees.

In London two people stood out

Anastasios

quite short

wavy brown hair

dark eyes

He was 35 and he spoke to me about leaving his home behind

Selling everything, his house, his car

He left his dog

and his family

“there are no jobs, no jobs in Greece now”

A cameraman who had worked in television

he explained that he was lonely

but with a pip of optimism still in him

he said finds comfort in small things,

like he’d smiled at a little boy on the bus earlier

and someone had let him pet their dog.

Then there was the woman

whose name I never did quite catch

she talked laboriously

heavy with some kind of respiratory problem

about how she had left Sierra Leone as a refugee.

Pursued into a neighbouring country.

She sang me a song which meant

“thank god for health and happiness”

and told me that her favourite person in the world was Tony Blair.

“He was the only one who ever cared about us”

“the only one. He said ‘come over here””

Tony Blair was her hero, because our country had offered her asylum.

In Stockton it was colder.

Somehow in a country I think of as small

compared to all of the others

I never really believe 3 hours on a train

will produce much of a temperature difference

I buy me and my 2 collaborators bobble hats from a charity shop on the high street.

Then we shiver standing, trying to catch people’s attention.

One of the first people who stop and speak to me

Is a young lad called Nicky.

Nicky tells me he’s just out of the army,

unemployed.

There’s a long thin scar on the right side of his face.

He’s from a local estate and when I ask about Stockton he tells me “everyone in this town is on the brown, all bagheads mate”.

I ask him what the biggest injustice in Britain is to him,

and he says it’s the NHS failing,

Nicky’s mate, largely silent next to him, suddenly speaks.

“it’s the immigrants, isn’t it? That’s why we vote UKIP”,

They explain how Stockton didn’t used to be like this, there used to open shops, jobs,

“but then they came, and now everything is worse.”

I ask Nicky about his regiment, he was 2 Yorks,

most of his family are in the armed services.

He says “the army changed my perspective,

they teach you all sorts of things,

like how lucky we are,

I can understand why people would want to come here, they have it a lot tougher.”

Nicky’s mate, as yet unnamed, speaks up again

He wants to study, earn enough points. Emigrate to Australia.

Nicky wants to be a business man

“not for the money though, money’s not the thing,

I want to find something I enjoy, something rewarding”

It occurs to me that if I were to paint a character of this person

without having met him

I might leave out details like his understanding.

In Bradford I steel myself

It is the third week of talking to strangers

and I am in a city I know mostly for race riots

Good food, post-industrial decline,

and George Galloway.

But several conversations into the day

and somehow everyone here is more positive.

There are still difficult stories:

a Pakistani boy-nearly-man

just out of prison

who speaks out of the side of his mouth

about the way the police “pick on pakis”

And a quiet spoken boy with facial pairings

fine dark black skin and university ambitions

always off to Leeds for gigs

laughs off his white mates never being stopped by the cops

when there isn’t a month goes by he’s not searched by them.

But I also meet a Bengali-Irish woman

who says

‘we’re all the same, all Bradford’

while her Pakistani-British husband smiles and nods.

A guy from Karachi who says ‘Bradford’s nice and bijoux’

And Fahard Ali.

Let me tell you…

Fahard Ali was a big man; round like a barrel of treacle.

He wore a mustard coloured flat cap,

aviator framed glasses,

reflective in the sunset.

I ask him what Britishness is to him.

When I get in, later, from talking to him I transcribe his words directly:

“I am british – it’s the language that I speak – […] being british is about the natural dominion of the island and the coast and the sea, the topography, the people, the struggles we’ve gone through, the literature, the architecture – Charles Barry, Lincoln cathedral – it’s not a singularity it’s a laminated effect of who we are – and let’s not forget it’s been 100 years since the beginning of the 1st world war – we’re also a product of that – we came out poorer, we lost 3 generations of men, had to rebuild ourselves, and empire and the loss of empire, the joining up of people through the commonwealth. You can be british if you’ve lived here four hours or if you’ve been here all your life – it’s about how you relate to it, and how you want to contribute to it. I feel happiest when I’m walking around the mills – those places – where things were happening – where cloth was being made. I’m happiest also when I’m bittersweet – those empty cathedrals of industry – it’s not that we were making something, it’s the hope and ambition it gave us. The people who came from the hay way into the city – it was about finding a better way to feed ourselves, clothe ourselves. There was something there – hope. I find myself happiest around industry. The biggest injustice is the loss of narrative. I say narrative over identity – because there are many identities. How we’ve got rid of narrative – become a homogeneous thing – […] we have no narrative of where we’ve come from, so we can’t tell where we’re going to. My favourite song is William Blake’s Jerusalem. Not as a religious song – the hope Blake puts in, and he identifies the english character of living on an island, and about hoping for something better – the reality is that the feet of god weren’t here, but we look forward to a Jerusalem of the mind.”

The next day

I speak to the director of the theatre I’m working in

and he says

“I think we feel together because we went through the riots”

There was a lot of healing that had to go on.

We saw this gulf in our communities

It hurt us.

it was hard. But the city is better now.

I am pro independence

I believe it will be good for Scotland.

And that is the only outcome that matters really.

But if you want to know what I think it means for England.

I think that it means there will be some people that stand on the same island, surrounded by the same sea, doing things differently.

picking neoliberalism out of their teeth

piece by piece

greater connection to Europe

positive immigration

internationalism

stronger trade

renewable energy

free education

an NHS with no private interest poison

no longer will Westminster be able to claim

‘there is no alternative’

They will be right there.

We are not losing our friends. They are still in the same place.

We still stand on the same island. Surrounded by the same sea.

They are not abandoning us to Tory rule.

Of the six Labour governments since 1945 only twice – in 1964 and February 1974 – was the party reliant on Scottish votes to help keep the Conservatives from office (my source is parliament.uk/

They are not divorcing us or leaving us.

The act of union 307 years ago that brought us together was built as a way of bailing out the super rich investors in the so-called Darien Scheme, and £Scots240,000 were handed out in direct bribes to ensure that act of union passed.

Sir John Clerk, an ardent pro-unionist and Union negotiator, observed that the treaty was “contrary to the inclinations of at least three-fourths of the Kingdom” [of Scotland].

If you want to use the hyper emotive language of betrayal, it was a forced marriage.

Within 100 years the clearances began, overseen by a British government,

Hundreds of thousands of Highlanders forcibly, violently and lethally ejected from their land.

We grew our sheep there instead.

Logged their forests

Took their oil.

infused their soil with nuclear experiments

We have not been nice to them.

Oh not you and me specifically

but England and Scotland are not you and me specifically.

And that’s how that kind of fucked up shit happens.

There are two ways to a world without borders.

One is expanding countries into unions into continents into international bodies.

The other is greater and greater devolution.

Until we reach the unit ‘a person’, and the understanding of our relationship to others

through contexts other than crossings;

the sounds our voices make,

the way we look when we do new thinking,

how we co-operate when we don’t have to.

I am pro independence for Scotland.

Thank you for listening to me.