It’s a bitterly cold, drizzly grey day in Stockton-on-Tees, and I’m walking as I talk to Naz (with a zed) about the place she’s from. It’s colder than I expected, somehow I never believe the UK to be large enough to have a substantial temperature difference (maybe its a midlander thing). As we walk, she talks, and I listen while adjusting the grey bobble hat I’ve bought from a Heart Foundation shop, absent-mindedly planning to cut the small tartan bow off the tassels as soon as possible.

Naz is short, she comes up to about my shoulder, and a minute or so ago I stood in the market square and asked if she has the time to tell me a story. I’ve explained that I’m collecting stories for a show I’m making at ARC theatre – most people have heard of the place, and if I get a chance to get past “I’m not selling anything and I’m not collecting for a charity” most people seem to acknowledge the theatre as an ok thing to be associated with and agree to chat. I explain to Naz I have some questions, just simple ones, to start from. Naz says that she has to be somewhere soon, but if I’m happy to walk and talk then she’s fine to help out. Happy to be recorded. We set out, pausing awkwardly at corners like you do when one person of two walking doesn’t know where you’re heading.

Naz has a light blue headscarf, pencil drawn black eyeliner, and is wearing a chunky black coat that almost buries her. I ask her some of the questions on my piece of paper. “Where would you say you’re from”? “Stockton, here” “What does that mean to you?” “It’s hard to say, it’s hard to say isn’t it? Stockton is… it’s multicultural, I’m proud to be from here, well, it’s difficult isn’t it, proud is a complicated word – this is my home, I don’t know anywhere else.” She weighs her words again and again, it’s her home, but sometimes she doesn’t feel welcome “around the time of the 7/7 bombings, it was difficult. My children suffered, things people said. People would see you in the street and only see one thing.”

Then earlier that day, shivering and pondering the charity shop I’ll buy 2 hats from in a moment (Keir, the 3rd member of the team and from Cornwall originally, brought his own), I stop two lads. I make an effort to stop people that I would feel a little threatened by as well as the ones I don’t mind asking, though invariably they turn out to be just as scary-not-scary as everyone else. These two are two I would probably cross the road from. If I saw them walk up the steps to the top of the bus when it was just me, I’d probably not get my iPhone out. And I’d think about security cameras, and whether or not the bus driver actually watches them. They look like the kind of people I’m scared would hurt me because I’m a woman.

They stop, and talk. There’s bravado, but they’re friendly and jokey. In the beginning mainly one of them answers me, but by the end both are joining in. Nicky tells me he’s just out of the army, both he and his mate are unemployed. There’s a long thin scar on the right side of his face. They’re from a local estate and when I ask them about Stockton they tell me “everyone is on the brown, all bagheads mate”. I ask them what the biggest injustice is in Britain to them, and they say it’s the NHS failing, “it’s the immigrants, isn’t it? That’s why we vote UKIP”, they explain how Stockton didn’t used to be like this, there used to open shops, jobs, “but then they came, and now everything is worse.” I ask Nicky about his regiment, he was 2 Yorks, most of his family are in the armed services. He says “the army changed my perspective, they teach you about all sorts of things, like how lucky we are, I can understand why people would want to come here, they have it a lot tougher.” Nicky’s friend, it turns out, wants to study, he wants to emigrate to Australia. Nicky wants to be a business man “not for the money though, money’s not the thing, I want to find something I enjoy, something rewarding”.

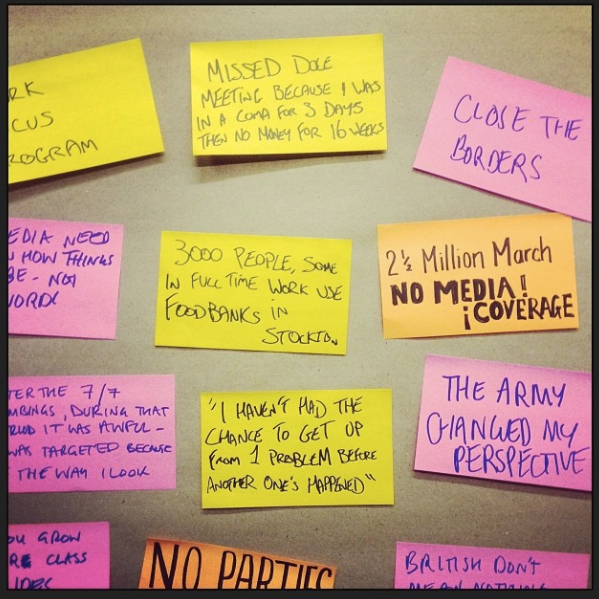

Two days later and I’m now staring at a transcription of these two conversations – we’ve had many others – extracts of all of them will make it into the Name Song which introduces every person who spoke to us. Things stand out – common themes, interesting outliers, but these two people… There’s something about Nicky and Naz which has encapsulated Stockton, for me. Sean and Keir have also relayed their conversations back to the room, we’ve talked about each person, described them, picked out certain things they’ve said, we’ve built a wall of post its of key images, sentences, reactions, and moved them around into collected headings.

We’ve done this in one city before – in South London, and we’ll do it in one more (Bradford) before trying to find a version of a show to in week four, in Leeds. London had a lot of themes. Londoners were more willing to stop and talk to us, and though there were homeless, jobless, people scratching a wage in the UK despite academic and professional acclaim in Pakistan or Greece; there was a greater variety of subject matter – people asked “what do you think the biggest injustice is today, in Britain?” answer mutlifold; poverty, bedroom tax, the way people treat me because I’m a drug addict, inequality, the way women are treated, that I had to leave everything behind because there were no jobs, post office privatisation, and the woman whose favourite person in the world was Tony Blair, because he was the only one to offer the Sierra Leone people asylum.

But back to Stockton, Wednesday. We look at our wall of post its. In London there were 12 or more themes, here, 5: Miscellaneous, hopelessness, unemployment, immigration, poverty. It’s tough to live here.

I’ve had an idea for a song; ‘From Here’. I sketch out what might be a chorus, and 4 verses – made up of words from Nicky followed by words from Naz. Keir and Sean play around with riffs and rhythm while I’m writing, then we come together, they like the chorus and we spend some time getting them to fit in with a rhythm that would work to launch the song – a mix of screamy phrases and fast-spoken verbatim quotes. Then we fit together a song around the spoken word which filters into explosions of sound and driving, thoughtful spacious music.

We it run through. We have a long conversation about the final reflective verse where I want to say that Nicky is just as complicated as the next person, just because some of his views might sound racist or intolerant to your average middle class lefty, he’s so much more than we think – I want to say that to myself and others. One of the hardest things is where to situate ourselves – declare our presence in the work – that the stories are all in response to questions we set, where our observations and words verbatim end and begin, and about our responsibility to individual people, and a whole place. Keir thinks I shouldn’t assume what anyone thinks not even ‘us’, and I sort of agree, except I sort of know I do think these things about Nicky, somewhere, and that’s why I make theatre like this. To face it myself, and show it to others.

In the end we find a way to say it which is fairer. Run it through once more. The last chorus rings out “I’m proud, I’m proud I live here”. And we move onto a song about all the people who said ‘no’ to our invitation to talk to us.

That week in Stockton I also run a workshop for local artists on ‘contemporary community theatre – in an increasingly digital, distributed, and urban age, what could community theatre look like’. In it, I quote Graeme Miller – a sound artist whose work like Linked and Desire Paths I class as a kind of digital/distributed community theatre.

“a place does not exist until it is imagined and named and that all of the copses, knolls and paths that have been walked and named are the mark points of human experience and the markstones of lives lived. These real spaces have become ‘unnamed’ with the passing of time, becoming less plausible than the centralised reality of the media and the transitory, frantic nature of living today.”

Miller talks elsewhere about places of passing – how the less we pass (and digital technology can often disrupt this as it offers us a better place of passing – passing people with whom we agree, or feel like we have a greater connection than just space) people, the more we believe the “centralised reality of the media” – the one that tells us about Them. The Racists. The Immigrants. The Tories. The Northerners. The Scottish. The Feminists. The Russians. The Women. The Men. Through Hollywood, internet, newspaper or daytime TV. The media will never be as true as the reality of individual people, nor could it be. That’s why we need to tell and listen to our own stories.

And that, roughly, is why Sean, Keir and I are shivering in the British rain, asking people about what it means to be where they’re from. What their hopes are. What angers them. And why we’re making punk songs about them. Because punk, like the ballad forms of old, is for and about everyone who wants it. The show, when finished, will be called Songs For Breaking Britain. We mean it both ways.

As Naz leaves me to walk toward the low run down terraces that carry out from the back of ARC, she says the words “it’s hard to be human, isn’t it”.

It is hard. And it is complicated. And we need to own that. Carry it. Pass it on.

Here’s that song (lyrics also included) recorded incredibly roughly. We’ve got 2 more weeks working on it in Bradford, then Leeds. Hopefully we’ll have a video for you at the end of it. Thanks for reading.

This project has been supported by and developed at OvalHouse, Theatre in the Mill, ARC Stockton, and Slung Low’s HUB. With support from Arts Council England’s Grants for the Arts, and Third Angel. And with additional collaborators Hannah Jane Walker and Alexander Kelly. Hannah Nicklin and Company is Hannah Nicklin, Keir Cooper, and Sean Arnold. The show is called Songs For Breaking Britain.