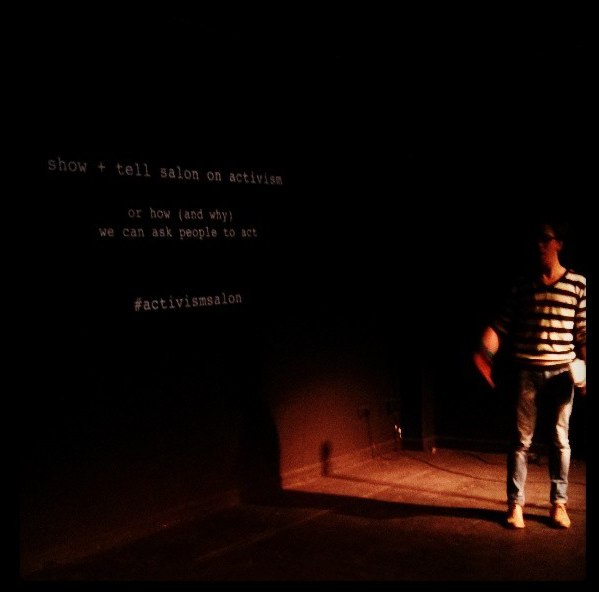

On Sunday I gave a provocation at a Salon hosted by Coney at Camden People’s Theatre, introduced by the lovely Tom Frankland (pictured). I was invited to respond to the question ‘how (can) we ask people to act?’, and offer my own question for discussion. Here is the thing that I said.

Audiences want to believe.

Audiences want to be told.

Audience want to play along.

Audiences turn away from ‘what is’ to conspire together to hold between them ‘what if’ – what if this were true, what if this was a different place and you were a different version of you.

The word ‘conspire’, by the way, means ‘to breathe together’.

Theatre is a rip in the space-time continuum held apart by collective hands. Even if it is just me, maker, and you, participant. In that space between, that hot metallic space between ‘what is’ and ‘what if’ we breathe together.

I read that meaning of ‘conspire’ in a book called The Most Radical Gesture. In it a woman called Sadie quotes an old drunk French philosopher who said:

Plagiarism is necessary. Progress demands it.

I’m not citing him out of purposeful irony.

There’s something there for me about co-creation.

I make community theatre. For some reason people insist on calling me a ‘digital artist’ but as far as I’m concern you might as well also call me a ‘water drinking artist’.

I make community theatre. Communities online and off.

3 years ago I collected stories of kissing in the rain online and wrote a soundwalk around them, designed to be listened to under a white umbrella in Piccadilly Gardens in Manchester. Incidentally that’s the only time I’ve been to Manchester and it didn’t rain).

In The Umbrella Project – yes umbrellas are a thing for me – 250 umbrellas were released into the wild of York with a number on them which when called, depending on the time of day, asked a different question; Tell me about York at night; Tell me about an encounter with a stranger; Tell me about a journey.

I also collected stories in person, and made 3 sound walks for different times of day, with each question’s answers as source material.

For Northern Big Board I spent 4 weeks in residence in a swimming and diving pool in Shipley near Bradford. The pool was suffering under government cuts and at the time were facing huge staffing upheaval – where, for example, 4 people with over 80s years experience of both working there and with one another were being interviewed for only 2 posts. And being interviewed for it by a friend.

I listened. I asked questions. Of both pool users and staff. Questions like ‘what does this place mean to you?’ ‘if you could have a plaque put up to you anywhere in the building where would you put it’ and ‘tell me about a time when you were the best of yourself’.

Dave told me about what it feels like to rip a dive – a perfect entry off a 10m platform – like silence he said.

Gee told me about looking up as he was administering CPR to someone who had had a heart attack to see his full team standing ready to take over and said ‘they were the best of me’.

Angie spoke of a place she had worked for over 35 years, the people she had seen grow up, have their own kids. She said ‘we’re like a family’ and that the cuts were like ‘a death in the family’.

I made 7 different interactive and non-interactive installations with their stories.

I set out to find common voices in these pieces – common experience, a common city, a community. But what I found – the overwhelming thing I found when I asked people for stories was the answer “oh, I haven’t got anything interesting to say.”

In York I asked a man with a zimmer frame – tell me about a journey – and he replied ‘oh, I’ve nothing to tell you.’ I reframed the question a couple of times and then he said ‘well, I have sailed around the world single handedly.’

No joke.

He told me ‘you can’t fight the ocean, you’d never win, you have to move with it.’

In Shipley people lit up when they saw their words on a plaque in their favourite place in the pool. They ran around trying to spot them all – came to me afterwards and asked if they could keep them. Their own words.

In Shipley when I asked one woman ‘tell me about a time you were the best of yourself’ she burst into tears at the idea that she might ever be worth enough to have an answer to that question.

Capitalism has stolen our stories.

It sells them back to us, like bottled water.

They are never about us.

They never listen.

Audiences want to believe.

Audiences want to be told what to do.

Audiences want to play along.

They turn away from ‘what is’ and carefully pass ‘what if’ between them.

I think the beginning of asking audiences to act is to make something they aren’t afraid to break. You’re not afraid to break things when you know they can be fixed. How they’re put together.

Something that doesn’t say ‘believe’ but ‘look’, that doesn’t tell, asks. Not ‘play along’ but ‘construct’ that in turning await from ‘what is’ turns us towards one another, within ‘what if’.

The work I told you about – my part in it – was constructing a mirror. Unimportant. The important part, I’ve discovered is the asking questions – in listening – but crucially in a way that tells people that they will be listened to. The work is the device that says ‘I heard you’.

The last thing I want to share with you is a definition of community I read in a different book. Another french dude – Jean Luc Nancy, in fact.

For Nancy community is not defined by space or proximity. No material communality – community – he says – should not be ‘productive’ infact it is impossible, indescribable, unavowable.

The clearest examples of community he talks about is that between lovers, and between the person dying and their companion. It is in the inability to truly accompany someone to their death in the knowledge you will take the same journey alone.

It is in the thrusting together ourselves together as we continue to do because we can never truly be close enough. The way I love you, this ache in the place I know in my head is not my heart is- is- this is- never enough never enough.

Community is the space between. Th space between what is – me – and what if – you, with your alike agency.

It is not the characters capitalism makes us to one another.

But hot, metallic possibility.

I am not you but what if

That has not happened to me but what if

I have not made that action but what if

In short; empathy.

These, I suggest, are the components of audience action:

- Knowing that you will be listened to

- Thinking you have something worth saying

- Listening to other people.

We cannot ask people to act. We can only offer them a space where they might recognise their being in the world, their being together with others, and their implication – the effect they might have upon that nexus. A space for action. A space of community.

We can offer them the community found in the in-between – in between possibility; in between you and me; in between idea and action – and we can offer them the ability to play with it without worrying it might break – by making it with them. Knowing that our coming together is impossible. Knowing the point is we try.

So, I have a question for you:

When was the last time you let someone change your mind?